We hear a lot of talk about commitment in Agile circles lately. But what is commitment? As it turns out, there are several meanings to the word. Leaving aside being committed to an asylum (which is where many of us will end if the methodology wars go on), the two dictionary definitions we care about are:

2a: an agreement or pledge to do something in the future

2c: the state or an instance of being obligated or emotionally impelled

(source: Webster’s Dictionary online)

I would like to refer to these two as “hard commitment” and “soft commitment”.

A hard commitment is essentially a promise, as in: “I commit to finishing this report by the end of the week”

People without hard commitments work without deadlines. Their work is done when it is done. An example is scientists or people working in Google-style companies.

(Note: Don’t confuse “no deadlines” with low productivity: not having a deadline means nobody forces you to predict a delivery date or conform to a schedule, not that you can get by without actually doing anything)

A soft commitment, by contrast, is an expression of an emotional state, of caring:

“I am commited to this relationship”

and more to the point:

“I am committed to this team” or “I am committed to this project”.

People without soft commitment are people who “just want to get their work done and go home”, typically because they either don’t enjoy their work or they are demotivated or burned out.

What type of commitment do we care about in the Agile world?

As it turns out, we seem to care about both. And we don’t distinguish too much between them. But there is a big difference between the two.

Hard commitments are typical in command and control, plan driven environments and dysfunctional organizations. This is a world where deadlines abound, monitored and enforced by armies of Gantt-chart wielding project managers who love to micromanage. In these projects, hard commitments are everything; and they translate into unmissable deadlines that themselves translate into long working hours, unsustainable pace, cutting on quality and eventually large turnover and technical debt.

A defining characteristic of these environments is that there is generally punishment envisioned for not living up to your hard commitments. From not making your bonus, to being publicly chastised by your boss, all the way to being fired; failing to comply with hard commitments is taken very seriously in these organizations because deadlines are the heart and soul of plan-driven management processes. Missing deadlines, simply put, costs money. Lots of it. Money in change management overhead, and money in penalties over contractual obligations missed.

Soft commitments, on the other hand, abound in startup type organizations, small projects and any environment where people are happy, work as a team, take pride in their work and care about the result.

Scrum: the all-commitment framework

Scrum is a framework that requires both soft and hard commitments from team members. The team is required to work as a team (for which soft commitment is required) and to commit to finishing a certain amount of work in one Sprint. Now, I don’t like hard commitments. I associate them invariably with command and control thinking. It is all too common to force people into accepting a hard commitment, by insinuating that bad things will happen if we don’t make a deadline or simply by giving an order: “make the deadline or you’re fired”.

But, in contrast to plan-driven processes, the difference is that in Scrum the hard commitment comes from within the team itself. It is not imposed from above. This is why many people see it as a “healthy” hard commitment.

Scrum and hard commitment failure

Have you ever seen a Scrum team that does not make its sprint goal? Of course you have. In fact, failure to meet hard commitments in Scrum is so common, Jurgen Appelo blogged about it today.

Let’s now compare Scrum with with plan-driven processes. What happens in Scrum if a team does not make its commitment?

I can envision any or all of the following happening if a team does not deliver all it promised:

- Nothing; since the Product Owner already knew they were behind schedule and adjusted her expectations a week ago.

- They get slapped in the buttocks by the Product Owner, who says something along the lines of “Bad boys! Bad boys! Don’t do this again!”

- The team feels bad about it. Someone might cry (yeah, right). They go into a retrospective to make sure it doesn’t happen again. Then they go for a beer.

See, in Scrum there is practically no external punishment for not delivering. Nobody will get fired. Nobody will lose their bonus. The only “punishment” is the team feeling more or less embarrassed because they overcommitted. This can hardly be seen as punishment when compared to a command-and-control organization.

Delivery in Scrum is governed by Systems Thinking. Essentially this means that if a team does not deliver all it promised, it is not the team that is at fault, because it is out of their control. It is the system that governs performance. (In this case, the system refers to the way work is chopped up and estimated and velocity is calculated.) “Not making it” only means that System capacity is lower than expected, or the system is unstable. The common solution is to reassess your expected Velocity to make it lower, and take less work next Sprint. And maybe to divide your work into smaller pieces. In any case, there can and should be no punishments dealt to the team.

So what is the value of making a hard commitment without punishment? What’s the point of committing to something, if everybody in the game knows that when we don’t keep the promise, nothing will happen?

Hard commitments in Scrum might, in practice, not be as ‘hard’ as they seem. Why try to make them look harder?

Kanban: the no-commitment framework

On the other side of the spectrum, we have the new Kanban ultra-lighweight framework. In Kanban there are no iterations and no hard commitments. You just limit Work In Progress and pull in work. Things are done when they are done, based on prioritization, cycle time and lead time. Proponents like to state that one of the benefits of Kanban is that it is a framework that (unlike Scrum) you can put in place in existing waterfall organizations without requiring disruptive change [1]. Kanban works along with the pre-existing method. For example, a tester just has test whatever he pulls into his plate and pass it along. No teamwork or commitment is initially required where it did not exist before. (Note to Kanban advocates: of course undoubtedly things will be better if there is a commited team; but the idea, if I understand correctly, is that Kanban will plug into the existing process, with or without a team).

Moving towards a “soft commitment only” framework

What would a framework in the upper left-hand quadrant look like? Soft commitment without hard commitment?

- It would require healthy, self-organized teams.

- It would require no deadlines, no “sprint goals”.

I believe both Scrum and Kanban can evolve in this direction.

For Kanban, it would probably mean adding the restriction that people have to work as a self-organized team. It becomes the responsibility of everyone to get work to fully done. This would maybe make Kanban less suitable for immediate implementation in waterfall organizations.

For Scrum, it would mean dropping the restriction that Teams have to “commit to delivering a certain amount of features during a Sprint” and going towards a more continuous flow paradigm. In this way, at Sprint Planning, teams would just pull the amount of stories they think they can do, but without explicitly committing to finishing them. They would do their best, and any unfinished stories would simply remain as top priority for the next Sprint. The Product Owner would monitor Velocity and progress during the Sprint, and adjust her expectations of what will be delivered accordingly. It is really just a simple change. Almost insignificant.

But is anybody interested?

Many people who practice Scrum correctly will swear by hard commitments. I have raised this issue several times and have always been fiercely rebutted. These people, who defend hard commitments with energy, are divided in two camps:

Camp A, the “Transitioning organization” camp: this is the camp that has two faces. Inwards they do Scrum, outwards (towards their external customers, or towards Senior Management) they maintain a plan-driven façade. They are in transition, having implemented Scrum internally but failing (or not yet getting around to) selling it to external stakeholders.

The problem with this camp is that many times they cannot or do not shield the Team from the external stakeholders. They pass on the Sprint scope as a hard commitment to the outside world, creating pressure on the team. Still, they are trapped with the problem that they cannot punish the team if it fails to achieve. Scrum in such a situation is very difficult.

Camp B”: the “People are Lazy” camp: this camp believes that people are not intrinsically motivated to do their best, and need someone with a whip (even if it is an imaginary whip in the form of a deadline) to keep whipping them in order to work hard and do their best. They think that people are naturally lazy, and if we would have a world without clear goals or deadlines, nobody would get anything done. It is surprising the number of software developers who think this way even of themselves.

This is more difficult to challenge. I don’t agree with this camp mostly on philosophical grounds. Basically I do not believe that this is true of human nature. Maybe I am idealistic. Or maybe they are right, and it is true that most people hate their job and are not intrinsically motivated to do their best. Or maybe we have been living too long in a command and control culture. So long that we have forgotten that work is one of the fundamental human rights, and many people actually like to work .

[1] David J Anderson, “Kanban: applying principles and evolving process solutions”, Lean and Kanban 2009 conference

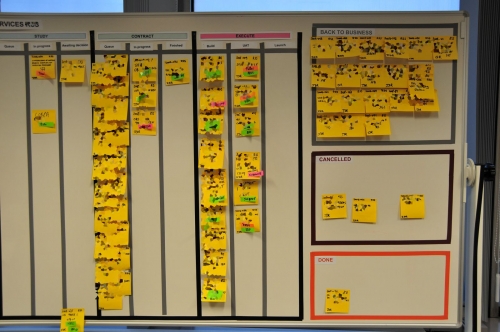

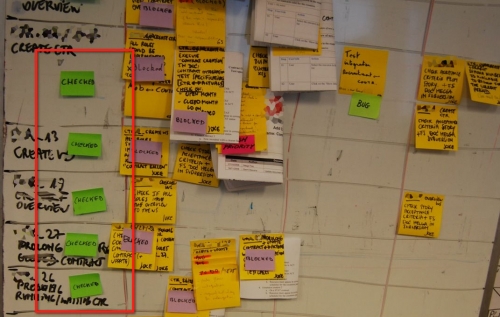

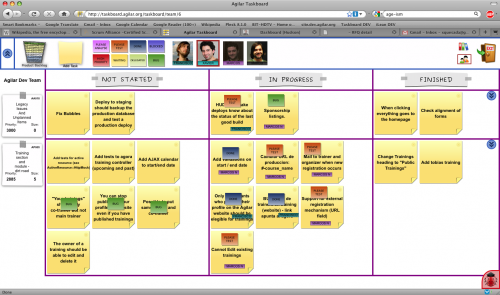

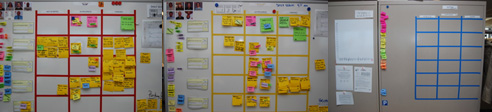

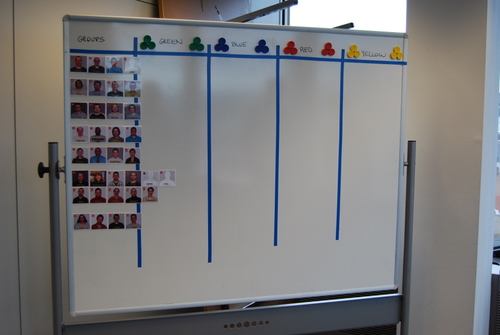

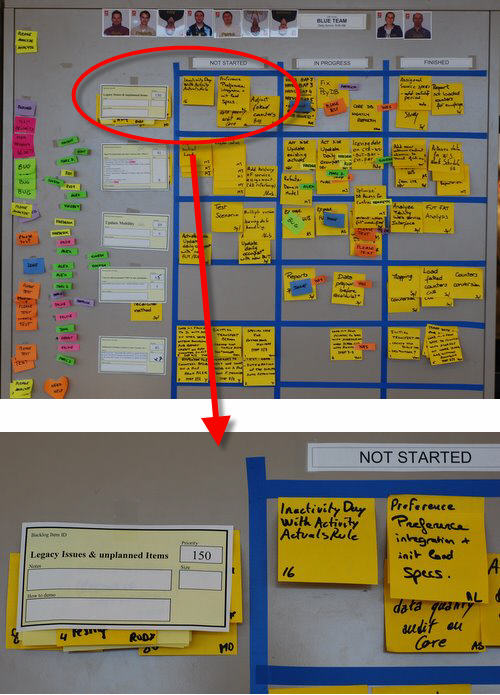

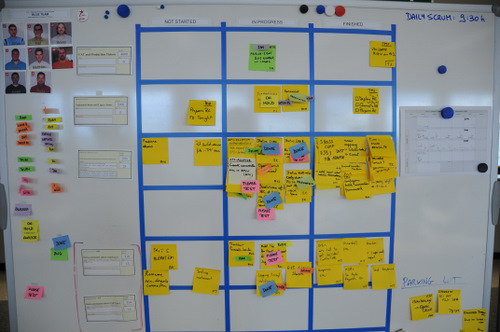

Let’s assume you found your definition of Team, and you have more than ten people in it. Since the ideal team size is 5 to 9, you probably want to split them up. But you don’t want to lose the concept of one Team. The recommended approach is to break them up into sub-teams. I will discuss some ideas for creating these sub-teams and for visualizing their work, while trying to keep and respect the spirit and vision of the one (big) Team.

Let’s assume you found your definition of Team, and you have more than ten people in it. Since the ideal team size is 5 to 9, you probably want to split them up. But you don’t want to lose the concept of one Team. The recommended approach is to break them up into sub-teams. I will discuss some ideas for creating these sub-teams and for visualizing their work, while trying to keep and respect the spirit and vision of the one (big) Team.

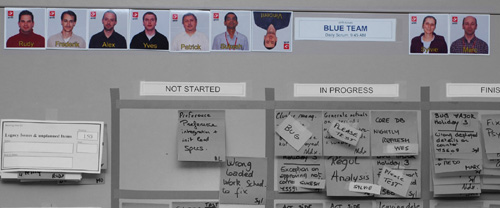

I take a decent picture of the person, crop it to a 750×750 pixel square, and insert their picture into a Photoshop template I made (available on request) with the logo of the company and the name of the person. Then I print it in glossy photo paper and plastify it (you can fit 12 pictures per A4 sheet). I cut the pictures out and finally I stick a piece of thin magnet to the back. The result is really good and sturdy, hard to explain in writing but the pictures look great, are solid and stick well to whiteboards. Many people ask for them as a souvenir when they leave the team!

I take a decent picture of the person, crop it to a 750×750 pixel square, and insert their picture into a Photoshop template I made (available on request) with the logo of the company and the name of the person. Then I print it in glossy photo paper and plastify it (you can fit 12 pictures per A4 sheet). I cut the pictures out and finally I stick a piece of thin magnet to the back. The result is really good and sturdy, hard to explain in writing but the pictures look great, are solid and stick well to whiteboards. Many people ask for them as a souvenir when they leave the team!

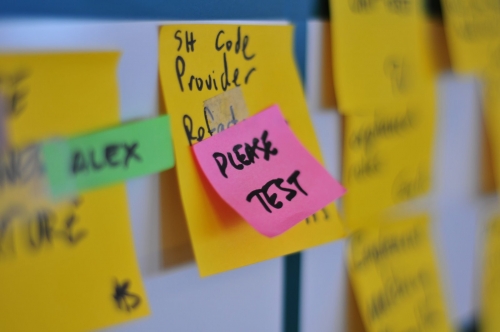

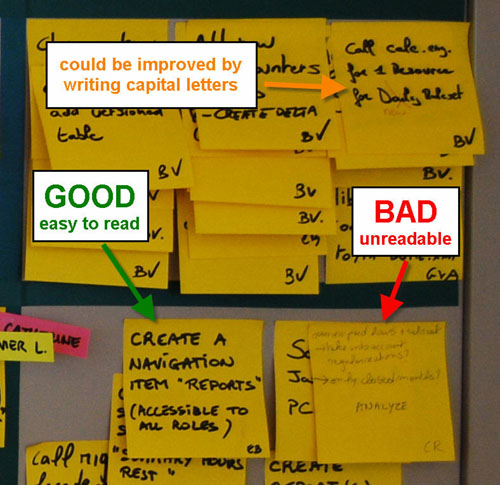

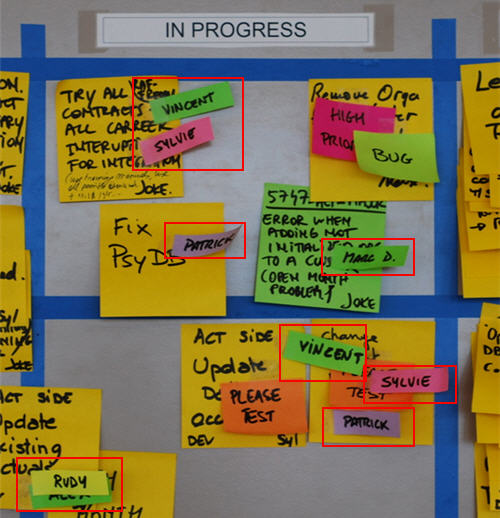

How to build the nametags: these are actually Post-It “Notes Markers” (product code 670/5) with a little bit of Magic Scotch tape at the end (because they’re not Super Sticky – just like status tags). They cost next to nothing and you get 100 of each color. They are 15 x 50 mm.

How to build the nametags: these are actually Post-It “Notes Markers” (product code 670/5) with a little bit of Magic Scotch tape at the end (because they’re not Super Sticky – just like status tags). They cost next to nothing and you get 100 of each color. They are 15 x 50 mm.

Recent Comments